Ultimate Axolotl Biology Guide: 14 Key Points How Their Bodies Work

When you watch an axolotl rest on the tank bottom, gills gently fluttering, you’re observing an animal that defies conventional vertebrate biology. They breathe through gills like fish but have lungs like terrestrial animals. They have bones and four legs like land vertebrates but spend their entire lives underwater. They’re salamanders that never grow up, retaining juvenile features while achieving sexual maturity.

Understanding axolotl biology isn’t just fascinating—it’s essential for proper care. Their unique anatomy and physaxolotliology dictate everything from water temperature requirements to feeding strategies to why certain health problems occur. When you know how their bodies work, you understand why specific care protocols matter.

This isn’t a biology textbook dissection. It’s practical knowledge that will make you a better, more informed keeper by revealing what’s actually happening inside your axolotl’s remarkable body.

Taxonomic Classification: What Axolotls Actually Are

Kingdom: Animalia (animals)

Phylum: Chordata (vertebrates with notochords)

Class: Amphibia (amphibians)

Order: Urodela (also called Caudata—salamanders and newts)

Family: Ambystomatidae (mole salamanders)

Genus: Ambystoma

Species: Ambystoma mexicanum

Common misconception: Axolotls are NOT fish. The nickname “Mexican walking fish” is misleading. They’re fully amphibian, more closely related to frogs and toads than to any fish species.

Evolutionary position: Axolotls belong to a family of North American salamanders that typically undergo metamorphosis. The axolotl’s permanent larval state (neoteny) makes it unique even within its own family.

Geographic origin: Endemic exclusively to Lake Xochimilco and previously Lake Chalco in the Valley of Mexico near Mexico City. They evolved in this specific high-altitude (7,300 feet) freshwater lake system with cool, stable temperatures.

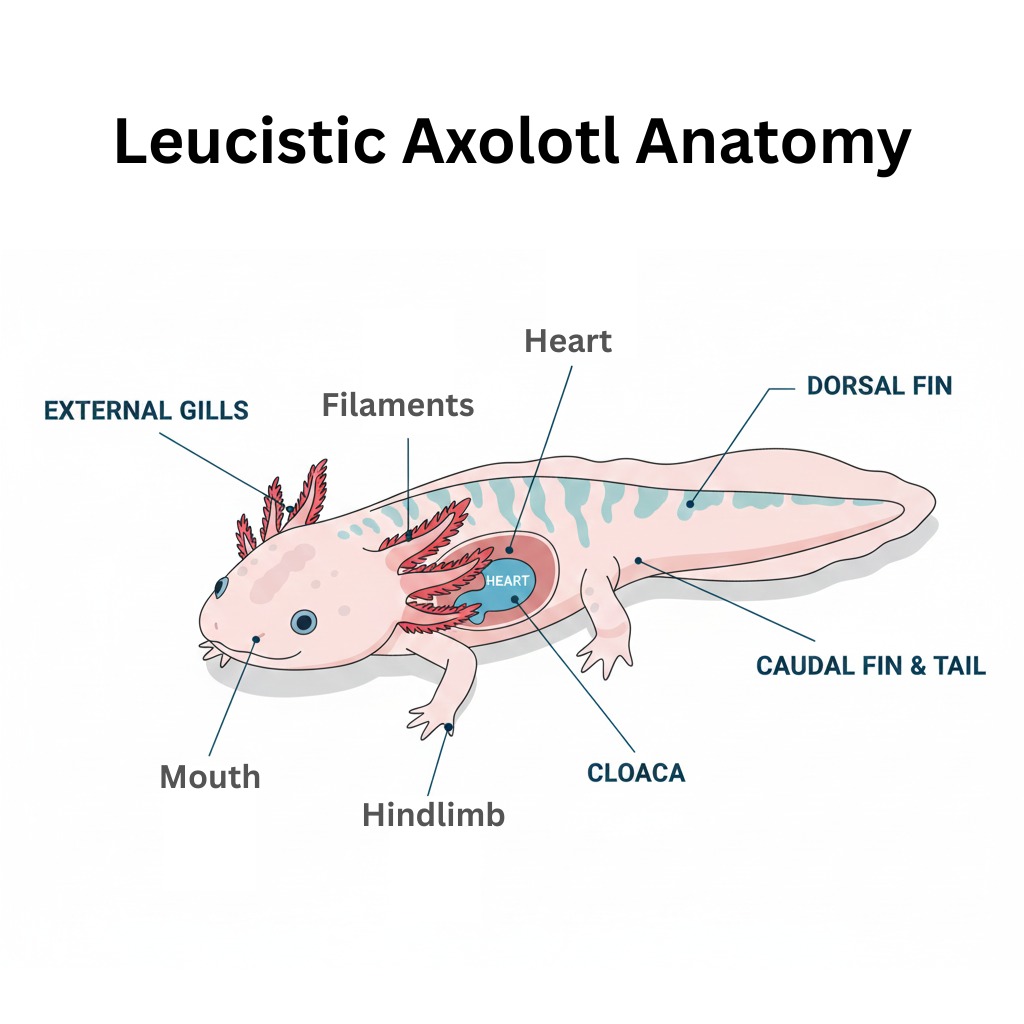

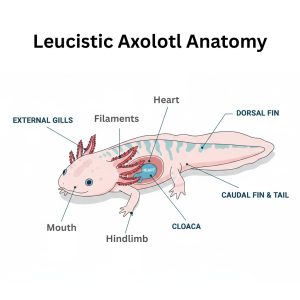

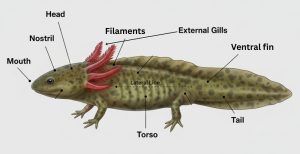

External Anatomy: Structure and Function

The Head and Sensory Systems

Eyes:

- Lidless (cannot close or blink—why they need dim lighting)

- Poor visual acuity (they’re not visual hunters)

- Can detect movement and light/dark changes

- Different morphs have different eye colors (dark eyes in wild-types and melanoids, red/pink in albinos, black in leucistics)

Nostrils (nares):

- Two external nostrils on top of snout

- Used for detecting chemical signals in water (olfaction/smell)

- Important for locating food—axolotls have excellent sense of smell

Mouth and jaw:

- Wide mouth with numerous small teeth (not for chewing—for gripping prey)

- Powerful suction feeding mechanism

- Can create vacuum to “inhale” food items

- Teeth arranged in rows across upper jaw, lower jaw, and roof of mouth

Lateral line system:

- Rows of mechanoreceptors along head and body

- Detects water pressure changes and vibrations

- Allows hunting in dark or murky water

- Why axolotls respond to movement near the tank even without seeing clearly

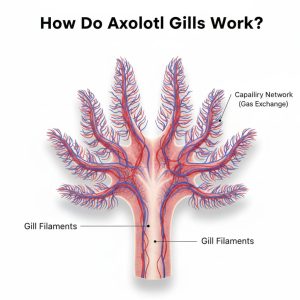

The Gills: Their Most Distinctive Feature

Structure:

- Three pairs of external gills (six individual gill stalks)

- Each gill stalk branches into numerous filaments (the “feathery” appearance)

- Filaments contain dense capillary networks for gas exchange

Function:

- Extract dissolved oxygen from water

- Expel carbon dioxide

- Surface area increases with gill fullness (healthy gills = maximum oxygen absorption)

Gill movement:

- Rhythmic forward flicking (clearing debris, circulating water)

- Continuous fluttering (extracting oxygen)

- Full extension and brightening when “firing up” (increased blood flow)

Color indicates health:

- Bright red/pink in light morphs = healthy, well-oxygenated blood

- Dark gills in melanoids = normal (pigmentation, not poor health)

- Pale, white, or gray gills (any morph) = poor water quality or illness

- Shrunken, stumpy gills = chronic stress, ammonia burns, oxygen deprivation

Why gills are so sensitive:

- Gill tissue is extremely thin (for efficient gas exchange)

- Direct exposure to water means direct exposure to dissolved toxins

- No protective barrier—pollutants, chemicals, and pathogens contact gill tissue directly

- Ammonia, nitrite, chlorine cause immediate chemical burns

Body and Limbs

Body structure:

- Cylindrical torso

- Dorsal fin running from behind the head to tail tip (larval feature retained in neoteny)

- Ventral fin along bottom of tail

- No scales or armor—skin is smooth and permeable

Limbs:

- Four legs with distinct digits

- Front legs: 4 toes each

- Back legs: 5 toes each

- Used for walking along substrate, not swimming (they’re bottom-dwellers)

- Can regenerate completely if lost—including bones, muscles, nerves, blood vessels, skin

Tail:

- Long, paddle-like structure

- Primary propulsion when swimming

- Stores fat reserves (healthy adults have thick, robust tails)

- Tip may curl slightly upward when stressed (warning sign)

Cloaca:

- Single opening for reproductive and excretory functions

- Located between back legs

- Males: enlarged, bulging from sides when sexually mature

- Females: flush with body, no visible bulge

Integumentary System: The Skin

Skin Structure and Function

Characteristics:

- Highly permeable (semi-permeable membrane)

- Absorbs water, oxygen, and dissolved substances directly

- Secretes protective mucus layer (slime coat)

Why permeability matters for care:

- Toxins in water (chlorine, ammonia, heavy metals) absorb through skin

- Medications can be administered via water (but also means accidental chemical exposure is dangerous)

- Handling transfers oils, soaps, lotions from human skin directly into their system

- This is why water quality is critical—they’re literally bathing in their environment

Mucus layer (slime coat):

- Thin protective coating secreted by skin glands

- Functions: prevents infection, aids in osmoregulation (water balance), reduces friction

- Damage from handling, strong currents, rough surfaces compromises this barrier

- Increased mucus production can indicate stress or irritation

Shedding:

- Axolotls shed skin regularly (every 1–2 weeks depending on growth rate)

- Old skin comes off in pieces or whole

- They usually eat their shed skin (it’s protein recycling)

- This is normal—not a health concern unless shedding seems excessive or skin doesn’t come off cleanly

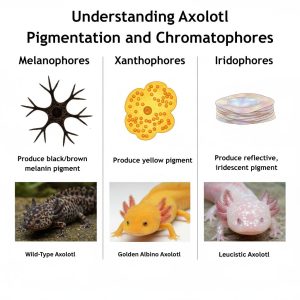

Pigmentation and Chromatophores

Three types of pigment cells (chromatophores):

1. Melanophores: Produce black/brown melanin pigment

- Present in wild-types, melanoids

- Absent in leucistics and all albino types

2. Xanthophores: Produce yellow pigment

- Present in wild-types, golden albinos, leucistics (to varying degrees)

- Absent in white albinos, axanthic morphs

3. Iridophores: Produce reflective, iridescent pigment

- Creates the shiny, speckled appearance in wild-types

- Absent in melanoids (why they appear uniformly dark)

- Present in most other morphs

Different morph colors result from combinations of which chromatophore types are present, absent, or modified genetically.

Visual breakdown of the three pigment cells: melanophores (black/brown), xanthophores (yellow), and iridophores (iridescent). The presence, absence, or modification of these cells through selective breeding produces all common morphs, from dark melanoids to golden albinos.

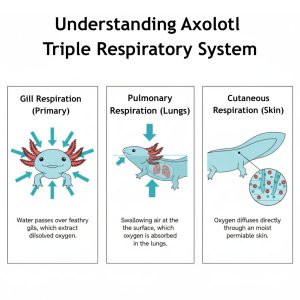

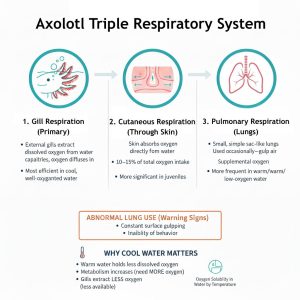

Respiratory System: Triple Breathing Mechanisms

This is where axolotl biology gets truly unusual—they have three different ways to breathe.

1. Gill Respiration (Primary)

- External gills extract dissolved oxygen from water

- Blood flows through gill capillaries, oxygen diffuses in, CO₂ diffuses out

- Most efficient in cool, well-oxygenated water

- This is their primary breathing method and why water quality/oxygenation is critical

2. Cutaneous Respiration (Through Skin)

- Skin absorbs oxygen directly from water

- Accounts for 10–15% of total oxygen intake in healthy adults

- More significant in juveniles (proportionally more surface area)

- This is why smooth, undamaged skin matters for health

3. Pulmonary Respiration (Lungs)

- Yes, axolotls have lungs despite being fully aquatic

- Small, simple sac-like lungs (not complex like mammalian lungs)

- Used occasionally—axolotls surface to gulp air periodically

- Provides supplemental oxygen, especially in warm or oxygen-poor water

- Juveniles use lungs more frequently than adults

Normal lung use:

- Brief surface visits every few hours

- Quick gulp of air, immediate return to bottom

- Fills lungs, provides buoyancy control

Abnormal lung use (warning signs):

- Constant surface gulping

- Inability to submerge after gulping

- Gasping behavior

- Usually indicates water quality problems (low oxygen) or temperature stress

Why cool water matters for breathing:

- Warm water holds less dissolved oxygen

- Their metabolism increases in warm water (need MORE oxygen)

- But gills extract LESS oxygen (because there’s less available)

- This mismatch causes respiratory stress above 68°F (20°C)

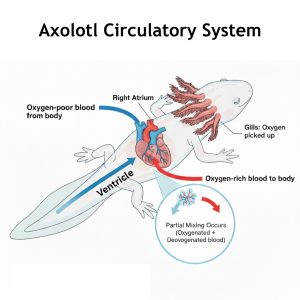

Circulatory System: Heart and Blood Flow

Heart structure:

- Three-chambered heart (two atria, one ventricle)

- Typical amphibian heart design

- Less efficient than four-chambered mammalian/bird hearts, but adequate for their low-metabolism lifestyle

Blood circulation:

- Oxygen-poor blood from body → right atrium → ventricle → gills (picks up oxygen) → body

- Partial mixing occurs in single ventricle (some oxygenated and deoxygenated blood mixes)

- This is why amphibians generally have lower metabolic rates than mammals

This diagram illustrates the circulatory pathway: oxygen-poor blood from the body enters the right atrium, moves to the single ventricle, is pumped to the gills for oxygenation, then circulates as oxygen-rich blood. The partial mixing in the ventricle explains why amphibians have lower metabolic efficiency than mammals.

Blood composition:

- Red blood cells contain hemoglobin (carries oxygen)

- White blood cells for immune defense

- Platelets for clotting (though they also rely on mucus for wound sealing)

Regenerative capacity:

- Can regenerate portions of heart tissue after injury

- Blood vessels regenerate during limb regrowth

- Research shows cardiac regeneration happens within weeks of injury (Faisal et al., 2024)

Why gill health affects circulation:

- Damaged gills = poor oxygen absorption

- Poor oxygen absorption = lower blood oxygen levels

- Lower blood oxygen = stress, lethargy, organ damage

- This is the cascade that makes water quality problems so dangerous

Digestive System: Processing Prey

Mouth → Esophagus → Stomach → Intestines → Cloaca

How they eat:

- Suction feeding: create negative pressure (vacuum) by rapidly expanding mouth cavity

- Food is inhaled whole—no chewing

- Teeth only grip, don’t break down food

- Tongue is small, doesn’t assist much in feeding (unlike mammals)

Stomach:

- Muscular, acidic environment breaks down food

- Produces digestive enzymes

- Food remains here for several hours

Intestines:

- Relatively short compared to herbivores (carnivore adaptation)

- Nutrient absorption occurs here

- Short intestinal length means food passes quickly—they need nutrient-dense food

Digestion time:

- 24–48 hours from eating to defecation in adults

- Faster in warmer water (faster metabolism)

- Slower in cooler water

- You should see poop within 1–2 days of feeding

Why they need high-protein diets:

- Short digestive tract doesn’t extract nutrients efficiently from plant matter

- Carnivore digestive system optimized for animal protein and fats

- Research confirms 45%+ protein diets provide best growth and health (Manjarrez-Alcívar et al., 2022)

Impaction danger:

- Swallowed gravel, substrate, or foreign objects block intestines

- They can’t vomit or pass large objects

- Blockage prevents waste elimination, causes bloating, often fatal without veterinary intervention

This diagram details their carnivore-adapted anatomy: mouth for suction feeding, short digestive tract optimized for protein, and complete path from ingestion to cloaca. Includes critical care notes on digestion time.

Nervous System and Brain Function

Brain structure:

- Relatively simple compared to mammals

- Well-developed olfactory bulbs (sense of smell)

- Optic lobes for vision (though visual processing is limited)

- Cerebellum for motor control and balance

Cognitive abilities:

- Limited learning capacity (they can learn feeding times, recognize keepers via smell/vibration)

- Classical conditioning works (associating you with food)

- No evidence of complex problem-solving or emotional bonding

- Memory appears short-term for most behaviors

Spinal cord:

- Extends through body and tail

- Controls locomotion, reflexes

- Remarkably, fully regenerates after severing—including functional nerve connections

- This regeneration is being studied intensively for human spinal injury research

Pain perception:

- Axolotls have nociceptors (pain receptors)

- They respond to harmful stimuli

- Whether they experience “pain” as mammals do is debated, but they clearly avoid injury

- Best practice: assume they feel discomfort and minimize stress/injury

Lateral line system (specialized nervous system structure):

- Neuromast organs along body detect water movement

- Helps locate prey, avoid predators, navigate environment

- This is why they react to vibrations near the tank

Skeletal System: Bones and Cartilage

Bone structure:

- Fully ossified (hardened bone) in adults

- Juveniles have more cartilage that gradually ossifies

- Lighter, less dense bones than terrestrial vertebrates (aquatic adaptation—don’t need to support body weight against gravity)

Skull:

- Flattened, broad skull

- Large eye sockets

- Openings for gills

- Jaw articulation allows wide gape for suction feeding

Vertebrae:

- Support body and tail

- Attachment points for ribs, muscles

- Part of what regenerates if tail is damaged

Limb bones:

- Forelimbs: humerus, radius, ulna, carpals, metacarpals, phalanges

- Hindlimbs: femur, tibia, fibula, tarsals, metatarsals, phalanges

- All regenerate perfectly if lost, including correct bone shape and joint formation

Calcium requirements:

- Bones need calcium for proper mineralization

- This is why diet needs good calcium-to-phosphorus ratio (>1:1)

- Earthworms provide this naturally; many pellets don’t

- Poor calcium = weak bones, metabolic bone disease, poor gill structure

Muscular System: Movement and Power

Muscle types:

- Skeletal muscle for voluntary movement (walking, swimming)

- Smooth muscle in digestive tract, blood vessels

- Cardiac muscle in heart

Movement patterns:

- Walking: slow, deliberate stepping along substrate

- Swimming: lateral undulation (side-to-side body waves) + tail propulsion

- Limited endurance—short bursts of activity followed by rest

Why they’re not active swimmers:

- Low muscle mass relative to body size

- Metabolism optimized for ambush hunting, not pursuit

- Aquatic lifestyle with neutral buoyancy means less muscle needed than terrestrial animals

Muscle regeneration:

- Complete muscle tissue regrowth during limb regeneration

- Includes reinnervation (nerve connections) and revascularization (blood vessel formation)

- Muscle fibers align correctly and regain full function

Excretory System: Waste Removal

Kidneys:

- Filter blood to remove metabolic waste

- Produce urine (dilute in aquatic animals)

- Maintain internal water and ion balance (osmoregulation)

Bladder:

- Stores urine temporarily

- Exits through cloaca

Primary waste product: ammonia

- Unlike terrestrial animals that convert ammonia to urea or uric acid (less toxic, requires less water to excrete), aquatic animals can excrete ammonia directly

- Ammonia is highly toxic, but in water it dilutes rapidly

- Most ammonia excretion occurs through gills, not urine

Why this matters for keepers:

- Your axolotl is constantly releasing ammonia into the water through its gills

- This is why the nitrogen cycle is critical—beneficial bacteria must convert that ammonia to less-toxic nitrate

- High water ammonia means your axolotl is essentially breathing in its own waste

- Kidney damage from chronic ammonia exposure is often irreversible

Reproductive System and Sexual Maturity

Males (sexually mature around 12–18 months):

- Testes produce sperm

- Sperm packaged in spermatophore capsules

- Deposited on substrate during breeding

- Enlarged cloaca is external indicator of sexual maturity

Females (sexually mature around 12–18 months):

- Ovaries produce eggs

- Can store sperm internally for weeks after picking up spermatophores

- Eggs fertilized internally before laying

- Can produce 100–600+ eggs per breeding

- Photoperiod changes (increasing day length)

- Temperature fluctuations (cooling then warming)

- Seasonal cues (even in captivity, some seasonal breeding patterns persist)

Sex determination:

- Genetic (not temperature-dependent like some reptiles)

- But full sexual differentiation takes 12–18 months—can’t reliably sex younger axolotls

Thermoregulation: Why Temperature Matters So Much

Ectothermic (cold-blooded) physiology:

- Body temperature matches environmental (water) temperature

- Cannot generate internal heat like mammals

- Metabolic rate tied directly to temperature

Temperature effects on metabolism:

| Water Temp | Metabolic Effect | Health Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 50–59°F (10–15°C) | Slowed metabolism | Reduced activity, slower digestion, potential lethargy |

| 59–68°F (15–20°C) | Optimal metabolism | Healthy activity, good appetite, efficient function |

| 68–72°F (20–22°C) | Elevated metabolism | Chronic stress, increased oxygen demand, immune suppression |

| 72–75°F (22–24°C) | Stressed metabolism | Severe stress, organ strain, high disease risk |

| Above 75°F (24°C) | Metabolic crisis | Organ failure, heat shock, death within hours to days |

Why they can’t “adapt” to warm water:

- Their physiology is calibrated for 60–68°F

- Warmer water = faster metabolism = higher oxygen demand

- But warm water holds LESS oxygen (physical property of water)

- They need MORE oxygen when LESS is available = respiratory crisis

- This isn’t about “getting used to it”—it’s physics and biology working against them

Cold tolerance:

- Can survive water down to near-freezing (though activity stops)

- More tolerant of brief cold exposure than heat

- However, prolonged cold (<50°F) causes metabolic shutdown and is also dangerous long-term

Growth and Development

Growth rates (with proper care):

- Hatchlings: 11–13 mm at hatching

- 1 month: 5–7 cm (2–3 inches)

- 3 months: 10–15 cm (4–6 inches)

- 6 months: 15–20 cm (6–8 inches)

- 12 months: 20–25 cm (8–10 inches)

- Adults: 23–30 cm (9–12 inches) average, some reach 35+ cm (14+ inches)

Factors affecting growth:

- Temperature (faster growth in warmer water within safe range, but with health trade-offs)

- Feeding frequency and quality

- Water quality (poor conditions stunt growth)

- Genetics (some lines are naturally larger or smaller)

- Stress levels

Growth continues throughout life:

- Unlike mammals that stop growing at maturity, axolotls are “indeterminate growers”

- They continue growing (slowly) throughout their lives

- Growth rate slows dramatically after 12–18 months

- Very old axolotls (10+ years) are noticeably larger than young adults

- Minis: small adults (15 cm/6 inches) due to malnutrition, poor conditions, or genetics

- Dwarfs: genetic condition causing stunted, disproportionate bodies

- Neither is healthy—they’re results of poor genetics or inadequate care

Lifespan and Aging

Captive lifespan: 10–15 years typical with good care; some reach 20+ years

Wild lifespan: Unknown (species nearly extinct, difficult to track), but likely shorter due to predation, environmental stressors

Aging characteristics:

- Metabolism slows (less active, eat less frequently)

- Some individuals may show mild organ changes

- Remarkably, regenerative capacity and cancer resistance remain high throughout life

- No significant cognitive decline observed

Research shows axolotls display unusual aging patterns, maintaining regenerative abilities and avoiding age-related diseases that plague most vertebrates (PMC, 2024).

[Place Image 2: “Axolotl Life Stages: Visual Progression from Hatchling to Adult” here]

Understanding Biology Improves Care

When you understand that your axolotl’s gills are thin, exposed tissue with no protective barrier, you understand why water quality is non-negotiable.

When you understand they can’t regulate body temperature and their metabolism is temperature-dependent, you understand why cooling equipment isn’t optional in warm climates.

When you understand their digestive system is short and optimized for animal protein, you understand why earthworms and high-protein pellets matter.

Biology isn’t just academic trivia—it’s the foundation of every care decision you make. The better you understand how your axolotl’s body works, the better equipped you are to provide what it actually needs.

That axolotl resting in your tank isn’t just a cute pet. It’s a biological marvel—a living example of evolutionary adaptation, neoteny, and regenerative capacity that scientists are still working to fully understand.

Respect the biology. Honor the complexity. Provide the care their remarkable bodies require.

References

Faisal, M., et al. (2024). The Genetic Odyssey of Axolotl Regeneration. International Journal of Developmental Biology, 68, 103-116.

Manjarrez-Alcívar, I., et al. (2022). Optimal diet for axolotl: Protein levels. Agro Productividad.

Ochoa, S., & Mickle, A. (2024). Axolotl Care Guide.

PMC. (2024). Advancements to the axolotl model for regeneration and aging.