There’s something almost otherworldly about an axolotl. Those feathery external gills rippling in the water, that permanent half-smile, the way they glide along tank bottoms like they’re walking on an invisible surface—they look like creatures from mythology, not biology. And in many ways, they are extraordinary: permanently juvenile salamanders that can regrow entire limbs, critical to cutting-edge regenerative medicine, and tragically, nearly extinct in their native habitat.

If you’re considering bringing an them into your life—or simply curious about these remarkable amphibians—understanding what they actually are, where they come from, and what they need is essential. This isn’t a goldfish. This is a critically endangered species with complex care requirements, fascinating biology, and a conservation story that should inform every ownership decision.

What Exactly Is an Axolotl?

Biological Identity: Neotenic Salamanders

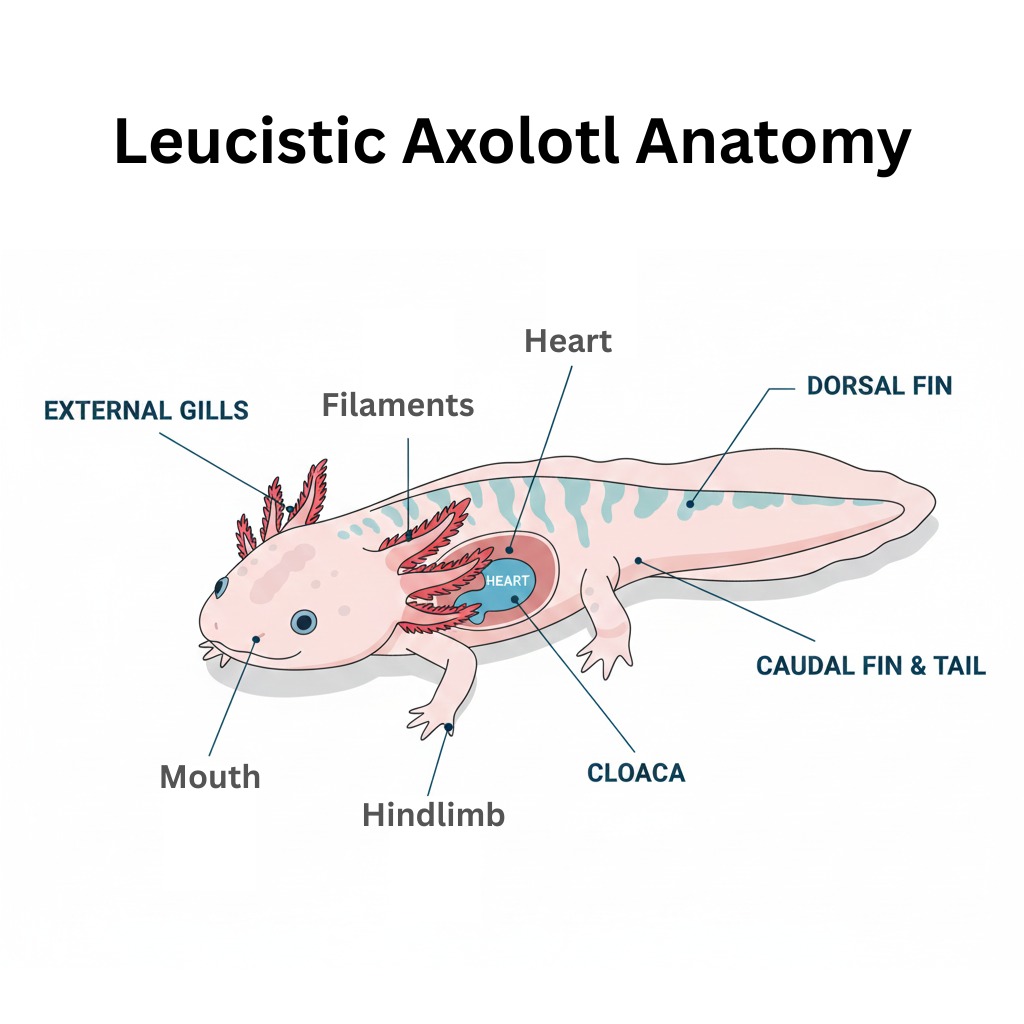

Axolotls (Ambystoma mexicanum) are neotenic salamanders, which means they retain their larval characteristics throughout their entire lives. While most salamanders undergo metamorphosis—losing their gills, developing lungs, and transitioning to land—they hit pause on this process and remain fully aquatic forever.

This biological quirk is caused by low thyroid hormone production. In other salamanders, thyroid hormones trigger metamorphosis. In axolotls, these hormones either aren’t produced in sufficient quantities, or their tissues don’t respond to them appropriately. The result? They keep their feathery external gills, their dorsal fin, their aquatic lifestyle, and their juvenile body plan for life.

- Size: Adults reach 15–20 cm (6–8 inches) on average, though some individuals grow to 30+ cm (12+ inches) with exceptional care.

- Lifespan: 10–15 years in captivity with proper care; some reach 20+ years. Wild lifespan is difficult to document given their critically endangered status.

Native Habitat: The Lakes of Xochimilco

Axolotls are endemic exclusively to the ancient lake system of Xochimilco and Lake Chalco in the Valley of Mexico, near what is now Mexico City. These high-altitude (7,300 feet) freshwater lakes once provided cool, stable, oxygen-rich water—ideal conditions for these cold-water amphibians.

Today, those lakes are largely drained or severely degraded due to Mexico City’s expansion. What remains of Lake Xochimilco is a network of canals—polluted, invaded by non-native fish, and supporting fewer than 1,000 wild axolotls according to recent surveys. The species is classified as critically endangered by the IUCN.

Wild vs. Captive Axolotls: Key Differences

Wild-Type Appearance

In their natural habitat, they display brown or tan coloring with gold speckles—camouflage perfectly suited to muddy lake bottoms. This mottled pattern helps them blend into their environment as ambush predators.

Captive Color Morphs

Decades of selective breeding in captivity have produced stunning color variations:

- Leucistic: Pink or white body with dark eyes (most popular pet morph)

- Golden albino: Bright yellow body with pink/red eyes

- White albino: Pale white with pink/red eyes

- Melanoid: Solid black with no iridescent speckles

- Copper, axanthic, and other rare morphs from selective breeding

Some captive axolotls even carry genetically engineered traits like GFP (green fluorescent protein from jellyfish genes), originally developed for research and now sometimes found in the pet trade.

Critical understanding: Captive-bred axolotls differ genetically from wild populations due to crossbreeding, selective breeding for color, and genetic mutations accumulated over 50–100+ years of captivity. They are not suitable for release into wild habitats and would not contribute to conservation of wild populations.

Extraordinary Regenerative Abilities

What Axolotls Can Regenerate

They possess regenerative capabilities that seem almost supernatural:

- Limbs: Entire legs, including bones, muscles, nerves, blood vessels, and skin—perfectly reconstructed

- Spinal cord: Functional neural regeneration with restored motor control

- Heart tissue: Cardiac muscle regeneration after injury

- Tail: Complete regrowth

- Brain tissue: Portions of brain including neural connections

- Eyes: Lens and retinal tissue

- Organs: Portions of liver, kidneys, and other internal organs

Most structures regenerate within 4–8 weeks, all without scarring—unlike mammalian healing which produces disorganized scar tissue.

Scientific Significance of Axolotl Regeneration

This regenerative capacity makes them invaluable models in regenerative medicine research. A 2025 study advanced understanding of gene activation in the nervous system using AAVs (adeno-associated viruses), revealing previously unknown brain-eye communication pathways vital for regeneration.

Researchers are working to understand the molecular mechanisms that allow axolotls to:

- Prevent scar tissue formation

- Activate dormant regenerative pathways

- Guide cells to rebuild structures in correct anatomical positions

- Maintain regenerative capacity throughout their entire lifespan

The hope is that understanding axolotl biology could eventually enable similar regenerative capabilities in humans—from limb regrowth to spinal cord repair to organ regeneration.

Unique Physiological Traits

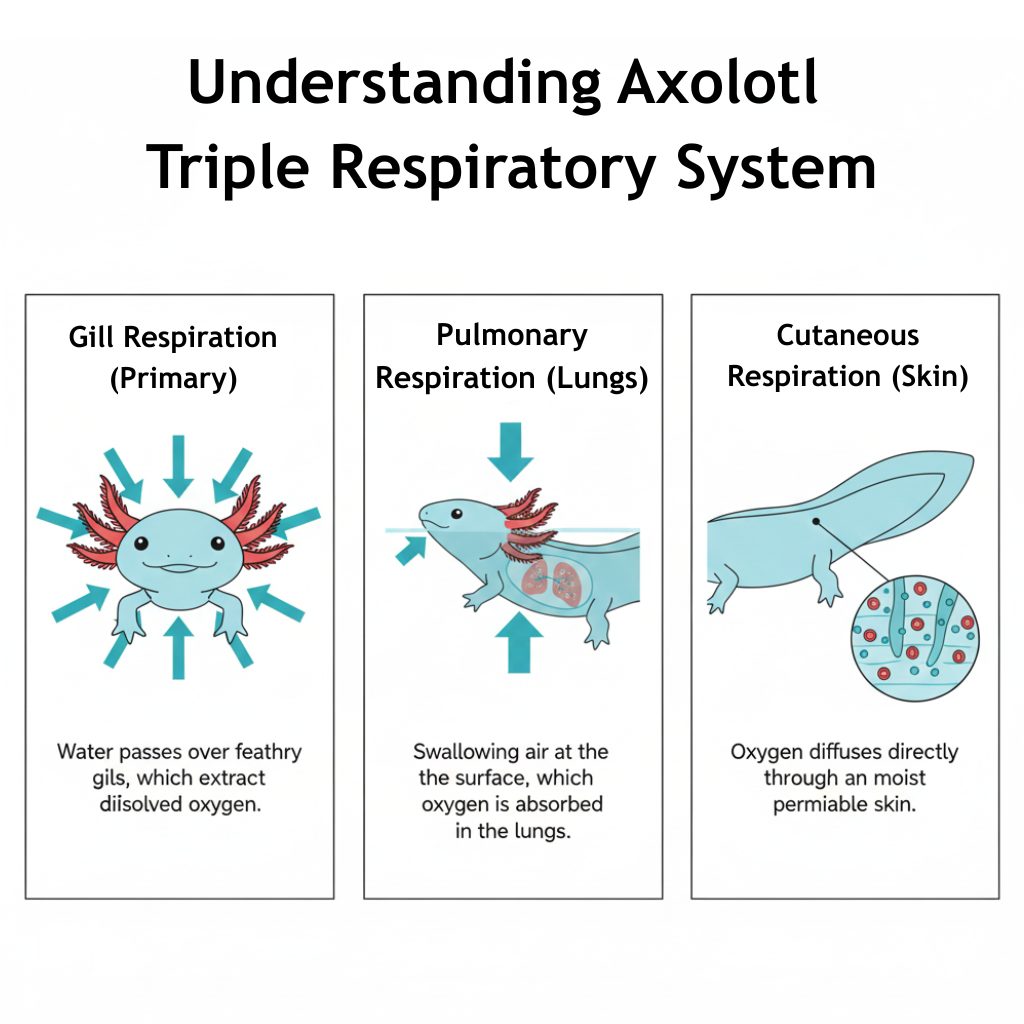

Triple Respiratory System

Axolotls have three ways to breathe—a remarkably flexible system:

- Gill respiration: External feathery gills extract dissolved oxygen from water (primary method)

- Cutaneous respiration: Skin absorbs oxygen directly (10–15% of total oxygen intake)

- Pulmonary respiration: Lungs allow occasional air gulping at the surface via buccal pumping (supplemental oxygen)

This triple system provides redundancy and adaptability to varying water conditions.

Feeding Mechanics

Axolotls are suction feeders—they create negative pressure by rapidly expanding their mouth cavity, literally inhaling prey whole. Adaptations for this feeding style include:

- Vestigial teeth: Small, numerous teeth for gripping, not chewing

- Gill rakers: Help filter and direct food

- Powerful jaw muscles for rapid mouth expansion

- Poor eyesight compensated by an excellent sense of smell and lateral line system (detects water movement)

They’re ambush predators by nature—sitting motionless, waiting for prey to pass, then lunging with surprising speed.

Conservation Crisis: The Wild Axolotl Population

Current Status

The wild axolotl population faces catastrophic decline:

- IUCN Classification: Critically Endangered

- Estimated wild population: Fewer than 1,000 individuals (some surveys suggest even lower)

- Habitat: Restricted to degraded canal systems in Lake Xochimilco

Threats to Wild Axolotl Populations

- Urbanization: Mexico City’s expansion drained Lake Chalco entirely and severely degraded Lake Xochimilco.

- Water pollution: Agricultural runoff, pesticides, heavy metals, and untreated sewage contaminate the water.

- Invasive species: Non-native fish like tilapia and carp compete for food, prey on axolotl eggs and juveniles, and alter the ecosystem.

- Low oxygen levels: Pollution and algae blooms reduce dissolved oxygen, stressing axolotls that require well-oxygenated water.

- Climate change: Alters water temperature and availability in an already stressed system.

Conservation Efforts and Recent Success

A 2025 breakthrough provided hope: captive-bred axolotls released into restored wetland habitats showed survival and weight gain. While predation risks persist and long-term survival remains uncertain, this represents the first documented success of captive-bred axolotls surviving in semi-natural conditions.

Key lessons from 2025 releases:

- Survivors thrived at specific temperature ranges matching their evolutionary adaptation to cool water

- Restored habitats with reduced pollution showed better outcomes

- Habitat restoration is essential—releasing axolotls into degraded canals alone isn’t sufficient

The hard reality: Captive populations in the pet trade don’t directly help wild conservation. Captive axolotls have diverged genetically and are unsuitable for release. True conservation requires habitat restoration, pollution control, invasive species management, and breeding programs using genetically pure wild-type lineages maintained separately in research institutions.

Axolotls as Pets: Suitability and Commitment

Who Should (and Shouldn’t) Own an Axolotl

Axolotls are suitable for:

- Experienced aquarium hobbyists familiar with water chemistry

- People in cool climates or with reliable air conditioning/chilling equipment

- Owners who can commit to weekly maintenance for 10–15+ years

- Those with financial resources for proper setup ($500–$1,200) and potential vet care ($200–$600+ per emergency)

Axolotls are NOT suitable for:

- Beginners with no aquarium experience

- Children as primary caretakers

- People in hot climates without cooling solutions

- Those seeking low-maintenance or interactive pets

- Impulse buyers attracted by their appearance without understanding requirements

Essential Axolotl Care Requirements

- Temperature: 60–68°F (15–20°C) consistently—this often requires chilling equipment in many climates

- Tank size: Minimum 40 gallons for one axolotl (larger is better)

- Filtration: Gentle flow (strong currents damage delicate gills)—sponge filters or baffled hang-on-back filters

- Substrate: Bare-bottom (safest) or fine sand under 1 mm grain size (only for axolotls 6+ inches long)—gravel causes fatal impaction

- Water changes: 20% weekly minimum to maintain water quality

- Diet: Earthworms, high-quality sinking pellets, occasional bloodworms—feed adults every 2–3 days

- Monitoring: Weekly water testing (ammonia, nitrite, nitrate, pH, temperature)

Common Axolotl Health Risks

Without proper care, axolotls are prone to:

- Impaction: From swallowing gravel or inappropriate substrate (often fatal without surgery)

- Ammonia/nitrite poisoning: From uncycled tanks or poor maintenance (causes gill burns, organ damage)

- Fungal infections: Secondary to stress or poor water quality (white cottony growth requiring treatment)

- Heat stress: From temperatures above 68°F (causes immune suppression, organ failure, death)

- Stress-related illness: From bright lighting, strong currents, handling, or aggressive tankmates

Critical requirement: Access to an exotics veterinarian experienced with amphibians. Not all vets treat axolotls—finding one before emergencies occur is essential.

Legal and Ethical Considerations for Axolotl Ownership

Axolotl Legality in the United States (2026)

Axolotls are illegal to own in:

- California (strict enforcement, significant penalties)

- Maine

- New Jersey

- Washington D.C.

Bans exist due to the risk of escape and hybridization with native salamander species, potential establishment of invasive populations, and concerns about impacts on local ecosystems.

Permits or registration required in: Hawaii, New Mexico, and Arkansas (owner registration).

Always verify current state and local laws before purchasing. Regulations change, and violations can result in confiscation, fines, or criminal charges.

Ethical Axolotl Ownership Principles

- Support reputable breeders: Choose breeders who document lineage, health screen breeding stock, and limit breeding frequency. Avoid mass breeders or those who can’t provide parent information.

- Never release into the wild: Captive axolotls are genetically unsuitable for wild habitats, carry diseases that could harm native species, and releasing them is typically illegal and ecologically harmful.

- Quarantine new additions: If adding to existing tanks, quarantine for 30+ days to prevent disease transmission.

- Avoid impulse purchases: Axolotls have surged in popularity due to social media and gaming culture. Popularity doesn’t change their complex care requirements or 10–15 year lifespan.

- Support habitat conservation: Consider donating to organizations working on Lake Xochimilco restoration rather than assuming pet ownership helps the species.

Understanding the Pet Trade Impact

The pet trade creates indirect pressure on wild populations by generating demand that historically encouraged wild collection, creating misconceptions that owning a pet axolotl contributes to conservation, and potentially introducing diseases or genetics into wild populations if released.

Ethical pet ownership prioritizes supporting conservation efforts financially, educating others about the difference between pet and wild populations, providing exceptional care for captive individuals, and never contributing to demand for wild-caught specimens.

The Paradox: Millions in Captivity, Nearly Extinct in the Wild

Here’s the reality every potential axolotl owner should understand: millions of axolotls exist worldwide in laboratories, classrooms, and home aquariums. Yet in their native Mexico, fewer than 1,000 survive.

This disconnect matters because:

- Captive populations don’t help wild conservation directly—genetic divergence makes them unsuitable for release

- True conservation requires habitat restoration, not just breeding more pets

- Popularity as pets hasn’t translated to meaningful wild habitat protection

- Most pet owners don’t realize their axolotl is genetically distant from wild populations

Owning an axolotl as a pet is a valid choice—but it should come with awareness that you’re caring for a domestic variant of a critically endangered species, not contributing to conservation of wild populations.

Making an Informed Decision Before Buying an Axolotl

Can You Provide the Right Environment?

- Consistent cool temperatures (60–68°F) year-round, even during heat waves?

- Weekly water testing and maintenance for 10–15+ years?

- Appropriate tank size (40+ gallons minimum)?

- Financial resources for setup, monthly costs, and emergency vet care?

- Commitment to learning complex water chemistry?

Do You Understand What Axolotl Ownership Really Means?

- They’re not interactive, cuddly, or social pets

- They cannot be handled except in emergencies

- They’re delicate and require constant environmental monitoring

- They have specific legal restrictions in some areas

- Your purchase does not contribute to wild conservation

If you answered “yes” to these questions and can commit to research-based, ethical care, axolotls can be fascinating and rewarding pets. Their biology is extraordinary, their care is manageable with proper preparation, and watching them thrive is genuinely remarkable.

But if you’re attracted primarily to their appearance, influenced by trends, or unprepared for the complexity of their needs, please reconsider. These animals deserve owners who understand what they’re committing to—not just for months, but for over a decade.

The Wonder and Responsibility of Axolotl Ownership

Axolotls are living contradictions: permanently juvenile yet capable of reproduction, critically endangered yet abundant in captivity, extraordinarily regenerative yet delicate in poor conditions. They’re creatures that challenge our understanding of biology, aging, and what’s possible in vertebrate life.

That wonder comes with responsibility. Every axolotl in captivity is a reminder of what we’ve lost in the wild—entire lake systems drained, habitats destroyed, a species reduced to canal remnants in one Mexican city. The contrast between their popularity as pets and their desperate status in nature should give every potential owner pause.

Choose ownership with eyes open to both the biological marvel and the conservation tragedy. Provide exceptional care. Support habitat restoration efforts. Educate others about the difference between pet populations and wild conservation. And remember that the greatest tribute to these extraordinary animals isn’t just keeping them alive in tanks—it’s ensuring their wild descendants have clean, protected habitats where they can thrive for generations to come.